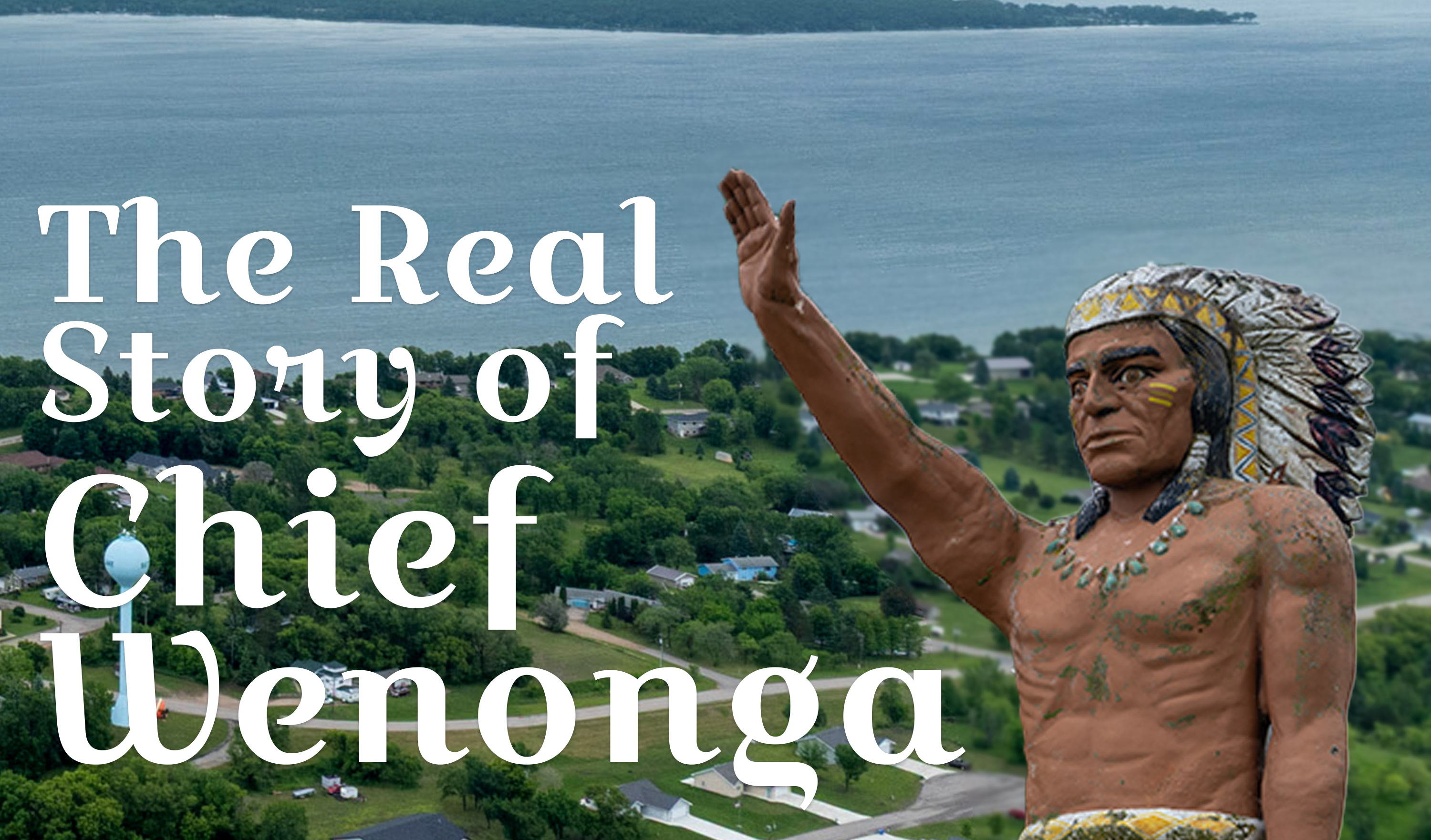

How a devastating 1795 battle created Minnesota's most misunderstood roadside attraction

Drive through Battle Lake, Minnesota, and you can't miss the 23-foot fiberglass warrior with his arm raised in greeting. Most visitors snap photos and move on, never realizing they're looking at one of Minnesota's most complex historical figures. The real story of Chief Wenonga isn't what the heroic statue suggests.

Wenonga's name means "Vulture" in the Ojibwe language, according to historian William Whipple Warren's 1852 account in "History of the Ojibway People." This wasn't a man born to leadership despite the statue's portrayal. Wenonga was a young Ojibwe warrior from the Leech Lake region, part of the Pillager Band during the late 1700s.

The era was marked by intense conflict as the Ojibwe migrated westward into territory long held by the Dakota nation. These weren't simple territorial disputes but fights over hunting grounds, wild rice beds and sacred sites that sustained entire communities.

In fall 1795, Chief Uk-ke-waus organized a 50-warrior raiding party targeting a Dakota settlement near what French traders called "Lac du Battaile." After a four-day journey south from Leech Lake, the Ojibwe spotted a small Dakota hunting party and gave chase through thick woods.

Three of the fastest runners, including Wenonga, burst onto open prairie to discover a massive Dakota village of approximately 300 lodges. The surprise attack had become a death trap—50 Ojibwe warriors faced potentially 2,000 Dakota defenders deep in enemy territory.

The Dakota response was swift. The outnumbered Ojibwe retreated to marshland near what is now West Battle Lake, fighting desperately from reed beds and shallow water.

Chief Uk-ke-waus made a fateful decision: he ordered younger warriors, including the wounded Wenonga, to escape while he and his three sons held off attackers. All four family members died that day. According to Warren's historical account, fewer than one-third of the war party survived.

The Ojibwe named the lake Ish-quon-e-de-win-ing: "Where But Few Survived."

Wenonga lived nearly 60 more years after the 1795 battle, reportedly taking pride in recounting the fight and claiming to have killed seven Dakota warriors. But there's complexity in a man spending decades retelling the worst day of his life—especially when that day involved watching his war chief and three sons die so he could escape.

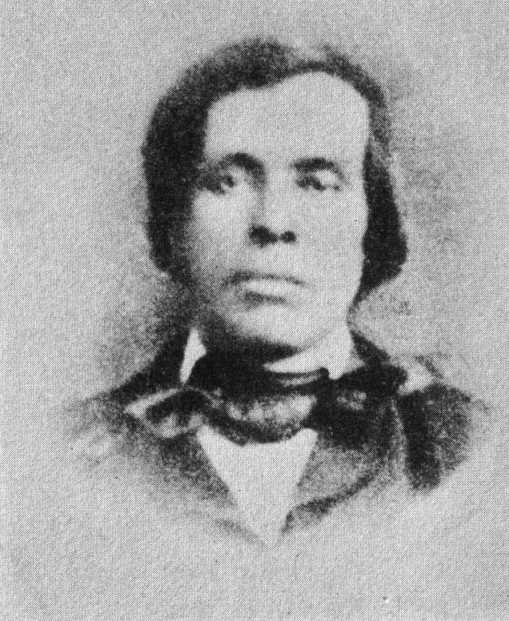

His story survives thanks to William Whipple Warren, the first Ojibwe historian. Born in 1825 to an Ojibwe mother and white trader father, Warren collected oral histories from tribal elders before his death at age 27 in 1853.

Warren noted that the Ojibwe, being deep in enemy territory, never returned to bury their dead. "Their bones are bleaching, and returning to dust, on the spot where they so bravely fought and fell," he wrote.

The uncomfortable truth about Battle Lake's statue: if historically accurate, it would depict a Dakota warrior. The Dakota won the battle decisively, successfully defending their village. The statue commemorates not a victor but a survivor of military disaster.

Wenonga wasn't the chief the statue suggests—that was Uk-ke-waus, who sacrificed himself for others. In Ojibwe society, leadership roles were complex, with war leaders, peace chiefs and band leaders having different authority. The title "Chief" on the statue oversimplifies historical reality.

The 1795 battle occurred during broader Ojibwe-Dakota conflicts that reshaped Indigenous geography across Minnesota. These wars weren't abstract historical events but involved real people making impossible choices in desperate circumstances.

Warren's documentation proved crucial—without his work collecting oral traditions, Wenonga's story would have been lost. His "History of the Ojibway People" remains a foundational text for understanding Great Lakes Indigenous history.

The annual Chief Wenonga Days festival celebrates around a statue that tells only part of the story. The real Wenonga was neither heroic figure nor simple victim, but a human being who survived when others didn't and carried that weight for six decades.

Wenonga's survival ensured that Uk-ke-waus' sacrifice wouldn't be forgotten. By living, sharing his story and maintaining his Ojibwe identity, Wenonga became an inadvertent guardian of memory.

When visitors photograph the statue today, they participate in remembrance stretching back over two centuries. The monument may not tell the whole story, but it prompts questions about Minnesota's complex history.

The real Chief Wenonga would likely be amazed to know he's still greeting travelers 200 years later. His true monument isn't the fiberglass figure but the fact that his story—complicated, human and tragic—survived at all.

For more Minnesota lake history and to experience these historic waters, visit Enclave Marine in Battle Lake, where our team connects past and present through comprehensive marine services.

Warren, William Whipple. History of the Ojibway People. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1984 (originally published 1852).

Wikipedia. "William Whipple Warren." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Whipple_Warren

Minnesota Historical Society. "William Whipple Warren." https://www.mnhs.org/people/william-whipple-warren

University of Minnesota. "Ojibwe Language Resources." https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/

Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe. Official Tribal Website. https://www.llojibwe.org/

Minnesota Historical Society. "Ojibwe People: History and Culture." https://www.mnhs.org/people/ojibwe

Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. "West Battle Lake Information." https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/lakefind/lake.html?id=56015300

Cultural Survival. "Ojibwe People: History and Culture." https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/ojibwe-people-history-and-culture

Minnesota Historical Society Collections. "Ojibwe-Dakota Conflicts." https://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10442843

National Park Service. "Native American History in the Great Lakes Region." https://www.nps.gov/miss/learn/historyculture/park_history_nativeamericans.htm

City of Battle Lake. "Chief Wenonga Days Festival." https://www.battlelakemn.com/